The tram operators of Sabino Canyon in Tucson, AZ are offering nighttime tours this summer. It’s part of an overall upgrade to the beautiful park located in the Santa Catalina Mountains and the Coronado National Forest. Along with upgrading to electric vehicles, the tour narration now comes with personal earbuds. This reduces the noise of the tour and allows the guides to share more detailed facts. I enjoyed this more informative talk. But one fact in particular caught my attention. Jellyfish have been found in Sabino Creek! Jellyfish in the desert? I had to find out more, and I absolutely had to share what I learned.

The Desert-dwelling Jelly

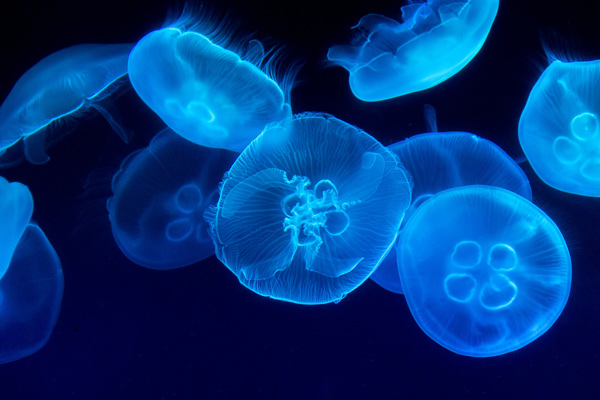

With my love of marine biology, I was excited by the thought of a native freshwater jellyfish being identified in this local creek. How did the jellyfish adapt to the inconsistent nature of desert bodies of water?

Once I returned home, I immediately searched online for the jellyfish of Sabino Canyon. Yes, this jellyfish was identified, but what I read saddened me. This wasn’t a native freshwater, desert-dwelling jellyfish. No, this was an invasive species.

The jellyfish in Sabino Canyon is Craspedacusta sowerbyi. This species was first found in 1908. Since then, it has spread to 43 states. C. sowerbyi, or the peach blossom jellyfish, is a hydrozoan cnidarian. Originally from the Yangtze basin in China, this jellyfish is now an invasive species found throughout the world, except for Antarctica.

More About the Invaders

This jellyfish has about 400 tentacles along the bell margin. The body is translucent with a whitish or greenish tint. The tentacles have nematocysts, which they use to capture prey. This jellyfish prefers calm and slow-moving freshwater bodies. C. sowerbyi is noted for showing up in new places.

C. sowerbyi consumes zooplankton caught with its tentacles. The venom injected by the nematocysts paralyzes the prey, the tentacle coils bringing the meal to its mouth. I am curious what zooplankton in Sabino creek it’s eating.

This jellyfish can reproduce both asexually and sexually. Interestingly, in the US, populations of C. sowerbyi are either all male or all female, suggesting no sexual reproduction is occurring.

During cold weather, the jellyfish polyps can become dormant as podocysts. Scientists believe that the jellyfish are transported as a podocyst in aquatic plants or animals to other locations. If they find the new environment suitable, they develop back into polyps.

I’m saddened that the jellyfish found in Sabino Canyon is an invasive species and doesn’t belong there. I don’t know if they plan to take action to eradicate the jellyfish or what damage it is inflicting upon the native environment. Being vigilant against intrusion by non-native plants and animals is a continual effort to protect our many environments.

My recent release, Guam: Return of the Songs, is all about how one invasive species can damage an entire ecosystem. But also, the hope to repair it. Introducing the brown tree snake to Guam destroyed many native animals in the island ecosystem. This book tells the story of that invasion and the return of Guam’s native birds, in both English and native CHamoru.

Reference: https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/specimenviewer.aspx?SpecimenID=168095