During the summer, two of my desert tortoises are allowed to roam outside. Zoe is a Sonoran desert tortoise, Gopherus morafka, and part of Arizona’s desert tortoise foster program. Cantata is a Sulcata tortoise, Geochelone sulcata. Native to sub-Saharan Africa, sulcata tortoises can reach 200 lbs. They’re also known as spur-thighed tortoises due to the spurs on their forearms. The spurs are designed to dig through hard ground, but can also cut through drywall. Despite this, they’re popular in the pet trade.

Cantata Tortoise, Den Digger Extraordinaire

When it comes to dens, Zoe is more than capable of digging her own. Still, she prefers to leave it to Cantata, who digs tunnels with amazing ease. I encourage her to dig in places that will cause minimal damage to irrigation systems or brickwork and such, but Cantata is stubborn and creates her den where she wants. Once she has a nice hole prepared, Zoe moves in to claim a spot. Consequently, Cantata then enlarges the tunnel so they both can live there comfortably, if not companionly. Having a tunnel big enough for them to pass each other keeps the tussles in check.

Hibernate or Brumate?

The lack of humidity that makes the hot desert summer days enjoyable is also responsible for the plunging nighttime temperatures in winter. During these cold months, some mammals hibernate, while reptiles may brumate. Hibernation and brumation both describe animals in a deep sleep. The term hibernation refers to warm-blooded animals, also known as endotherms, while brumation refers to cold-blooded animals, who are ectotherms.

Strange Bedfellows

When the wintry chill arrives in the Sonoran Desert, some of my reptilian family members head for their brumation beds. These beds are better known as underground dens. Tortoises dig their own dens, while other reptiles, such as rattlesnakes, slither in to join them.

Prey animals will also spend the winter with predators. That’s right, animals that are mortal enemies in the summer will often share dens in the winter!

Let Me In!

I’ve gotten the impression that Zoe’s previous foster parents allowed her to brumate inside. Each fall, as the temperatures tell her it’s time to prepare for brumation, she heads for my back door and makes it clear that she wants in. She only does this when it’s time to brumate.

In past years, I made her brumate outside, as wild tortoises do. She’d eventually give up trying to come indoors, dig out her den and close it up behind her. Last year, however, she made it clear that she was only coming indoors. To send a message, she went to a previous winter den, halfheartedly dug out the entrance, and then jammed herself in, making sure she stuck halfway out. Message received. I let her in and she brumated in my bedroom.

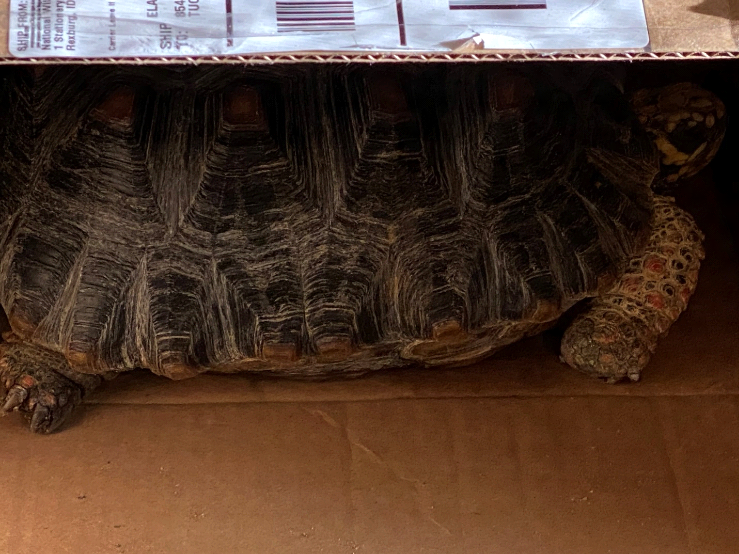

This year, I knew she’d pull the same trick, so when the nighttime temperatures began to drop I brought her inside. For a few weeks, she roamed around, continuing to eat, until finally, it was time for her to brumate. I always wonder how these animals know when it’s time since the indoors temperatures remain the same. I’m sure it has to do with circadian rhythms and sunlight length, etc. At the same time, both Cantata and Zoe found a place to brumate and have snuggled together for the winter…in a cardboard box, in my kitchen!

Since they settled in, they haven’t left their box. At least I can keep an eye on them this winter. It seems that summer’s reluctant tunnel mates are now winter’s willing bru-mates.